OPERATION

CROSSROADS Atomic Weapon Tests

Bikini Atoll (July 1946)

Operation Crossroads was the first full scale military testing of atomic devices to get a good understanding of their destructive and radioactive power. The military learned a little about atomic weapons awesome power from its earlier Trinity test and from the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki but in the rush of war, the focus was on a destructive weapon to help end the war.

Now with the war over, the military needed to better understand this new weapon and its effects - especially on naval targets so they could properly utilize nuclear weapons in the future. Accordingly, the Joint Chiefs of Staff requested and received presidential approval to conduct a series of nuclear tests during the summer of 1946. Vice Admiral W. H. P. Blandy, head of the test series task force, proposed calling the series Operation "Crossroads." "It was apparent," he noted, "that warfare, perhaps civilization itself, had been brought to a turning point by this revolutionary weapon."

Experience

with the extreme radiological hazards of Trinity and the damage caused

by the two bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki strongly influenced

the decision to locate Crossroads at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands

of the central Pacific, far from all major population centers. Bikini

was a typical coral atoll. With a reef surrounding a lagoon of well

over 200 square miles, Bikini offered ample protected anchorage for both

a target fleet and support ships.

Experience

with the extreme radiological hazards of Trinity and the damage caused

by the two bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki strongly influenced

the decision to locate Crossroads at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands

of the central Pacific, far from all major population centers. Bikini

was a typical coral atoll. With a reef surrounding a lagoon of well

over 200 square miles, Bikini offered ample protected anchorage for both

a target fleet and support ships.

While the location was ideal from a safety perspective, it offered a series of challenges that needed to be overcome. First, its great distance from the United States created a huge logistical challenge to get all the supplies, equipment and test ships to the atoll. Secondly, the humidity level at Bikini is quite high and that created a variety of problems with the delicate recording equipment that would be used to record and photograph the events.

The last problem, removal of the native population of 162 and bringing in observers was the smallest of the three problems. In fact, the audience included a large number of journalists, scientists, military officers, congressmen and a handful of foreign observers.

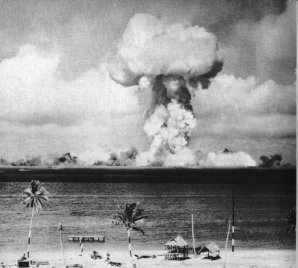

The

first test, Shot "Able" (right), was a plutonium based nuclear bomb dropped

from a B–29 on July 1. It performed as well as the plutonium devices used

at Trinity and Nagasaki. While the device was capable of huge

destruction, the test results were disappointing. Able failed to live

up to its pre-test publicity buildup for a few reasons. Partly this

was because expectations for the blast had been too extravagant and observers

were so far from the test area (for safety reasons) that they could not

see the target array that was being studied. And partly it was because

the drop had missed the anticipated ground zero by some distance and the

blast sank only three ships. Because of these issues, the perception

was that the atomic bomb was nothing really special - certainly no more

special than any of the other large bombs that the military had in its

arsenal. (Click here

for a brief video of the Able test.)

The

first test, Shot "Able" (right), was a plutonium based nuclear bomb dropped

from a B–29 on July 1. It performed as well as the plutonium devices used

at Trinity and Nagasaki. While the device was capable of huge

destruction, the test results were disappointing. Able failed to live

up to its pre-test publicity buildup for a few reasons. Partly this

was because expectations for the blast had been too extravagant and observers

were so far from the test area (for safety reasons) that they could not

see the target array that was being studied. And partly it was because

the drop had missed the anticipated ground zero by some distance and the

blast sank only three ships. Because of these issues, the perception

was that the atomic bomb was nothing really special - certainly no more

special than any of the other large bombs that the military had in its

arsenal. (Click here

for a brief video of the Able test.)

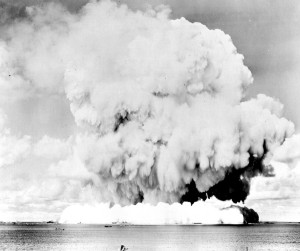

The second test, Shot "Baker," turned out to be much more impressive.

It detonated ninety feet underwater on the morning of July 25 causing

Baker to produce a spectacular aerial display. In fact, it was so powerful,

it severely damaged the seventy–four–vessel fleet of empty ships and spewed

thousands of tons of water into the air. As with Able, the test

yielded explosions equivalent to 21,000 tons of TNT. Baker, as one

historian notes, "helped restore respect for the power of the bomb." (Click

here

for a brief video of the Baker test.)

The second test, Shot "Baker," turned out to be much more impressive.

It detonated ninety feet underwater on the morning of July 25 causing

Baker to produce a spectacular aerial display. In fact, it was so powerful,

it severely damaged the seventy–four–vessel fleet of empty ships and spewed

thousands of tons of water into the air. As with Able, the test

yielded explosions equivalent to 21,000 tons of TNT. Baker, as one

historian notes, "helped restore respect for the power of the bomb." (Click

here

for a brief video of the Baker test.)

Because

it exploded under the water, Baker also created a major radiation problem.

The test produced a radioactive mist that deposited radioactive products

on the target fleet in amounts far greater than had been anticipated.

As the Joint Chiefs of Staff evaluation board later noted, the contaminated

ships "became radioactive stoves, and would have burned all living things

aboard them with invisible and painless but deadly radiation."

Because

it exploded under the water, Baker also created a major radiation problem.

The test produced a radioactive mist that deposited radioactive products

on the target fleet in amounts far greater than had been anticipated.

As the Joint Chiefs of Staff evaluation board later noted, the contaminated

ships "became radioactive stoves, and would have burned all living things

aboard them with invisible and painless but deadly radiation."

Decontamination presented a significant radiation hazard, and, as a result, over a period of several weeks personnel exposure levels began to climb to dangerous levels. A worried Stafford Warren, who headed the testing task force's radiological safety section, concluded that the task force faced "great risks of harm to personnel engaged in decontamination and survey work unless such work ceases within the very near future." With hard data to back him up, Warren was able to get decontamination operations to cease.

A planned third shot, to be detonated on the bottom of the lagoon, was canceled. Able and Baker were the final weapon tests conducted by the Manhattan Project and the last American nuclear weapons tests until the Atomic Energy Commission's Sandstone series began in spring 1948.